A walkthrough for making your own operating system in Rust, inspired by Philipp Oppermann's blog "Writing an OS in Rust".

View the book

The tutorial uses mdBook. The latest version of this tutorial, deployed from the main branch, is available at https://rust-os-tutorial.netlify.app.

Version

You are viewing v2.

🚧 In Construction 🚧

Feel free to follow this tutorial. New parts will be added! New parts might also come as a new tutorial version, in which case you might have to make some adjustments to your OS first before following the tutorial for new parts.

Contribution Welcome

This is a tutorial and meant to be a community project. Contributions are welcome. Some examples are:

- Fixing typos in tutorial or code

- Making improvements to tutorial or code

- Adding translations

- Making a nice website for this tutorial

- Adding new parts (but make an issue first so we can plan it first)

Git branches

main is where all of the tutorials go (the "production" branch for tutorials). The tutorial uses mdBook. You can read about its installation and the commands to generate the book. dev is similar to main, but it is a development / preview branch.

code is the branch which contains the code that goes along with the tutorial. Each commit is 1 part of the tutorial. To edit main and code at the same time, you can use git worktree add code --guess-remote, and the code branch will be in the code folder.

ming part number. code-dev is the corresponding development branch.

next is an OS that is very similar to the tutorial OS where I try out implementing new things. It is kind of a preview of what will come to this tutorial. It is kind of messy because I might rebase next based on the tutorial, but right now it's based on an old tutorial version.

Git and contributing

Adding a new part (in the end)

Pretty simple:

- Add a commit to the

mainbranch- Create

Part ## - <Title>/README.md, plus you can add additional files such as images.

- Create

- Create a commit on

code. Here you can make changes to the OS code.

Changing existing parts

If you are changing existing old part, or inserting a part before the latest part:

- Update the

mainbranch- Modify the part that you are changing

- If you are inserting a part before the last part, renumber all of the next parts

- If code in the next tutorials changes, update those too

- Update the

codebranch- Use

git rebaseto edit the commit for the part you are modifying

- Use

Since this is full of rebasing, to save time, talk with me first before making a significant change, even if you are adding a new part (because someone else could also be adding a new part at the same time.)

Viewing the old version

If you started viewing the v1 version and want to continue it, you can view the v1 git tag. You can view the parts at v1p<n> where n is the part number. Still, I would recommend starting over from v2.

Introduction

Do you want to write your own operating system, from hello world to automatic updates? Do you like Linux and Redox OS, but want to make your own operating system from the ground up, the way you want? Do you want to write your OS in Rust? Then this tutorial is for you!

Who this is for

You don't need to know Rust but you need to be able to learn. This tutorial will not teach you Rust, but it will provide links to learn if you don't know.

Setting up the Development Environment

If you are using NixOS, then most of this will be very easy for you.

You will need...

- Rust installed.

- A code editor. This is entirely your preference. I would recommend Vscodium with rust-analyzer, or Zed.

- Git

If you are using NixOS, you can just run nix develop in the directory containing flake.nix. I recommend using direnv and nix-direnv so you can simply run direnv allow once and then your development environment will be set up automatically every time you enter the folder. If you're using Vscodium I would also recommend using the direnv extension.

Boot Loaders

The first thing we need to do is give our operating system control of the computer.

The entry-point of an operating system is an executable file. When a computer turns on, the first thing it runs is the firmware. Modern computers have UEFI firmware, and very old computers have BIOS. The firmware looks for operating system executable files in various locations, including internal SSDs and HDDs, as well as external locations such as USB disks or servers on the network.

The protocol for giving control of the computer to an operating system is different for BIOS and UEFI. Working with BIOS and UEFI can be very complicated. Operating systems have boot loaders which go between the firmware and the actual operating system's entry point. The firmware gives control to the boot loader. Then the bootloader can do its own stuff, and eventually looks for the operating system entry point and gives control to it.

There are many boot loaders and boot loader protocols. A boot loader protocol basically states "this bootloader will boot operating systems in this way", and specific boot loader implementations can implement common boot protocols. Some examples of boot loader protocols are:

- GRUB

- Multiboot

- The Linux Boot Protocol

- Limine

- The Rust OSDev Bootloader, written for https://os.phil-opp.com/

In this tutorial, we will use Limine, because it is modern, simple, and makes writing an OS easy for us.

Limine

By default, Limine simply calls an entry function in our operating system. We can ask Limine to do more things for us, such as setting up other CPUs to run our operating system's code on. Before calling our entry function, Limine goes through our executable file, checking for special data which are called Limine requests. Limine then does the set-up that the request asked it to do, and fills that area in the executable's memory with its response.

It's important to know that Limine requests and responses are not like HTTP requests and responses, where the client's code and server's code is running at the same time. All Limine requests get processed before our OS starts, and once our OS starts, Limine is not running anymore, and all Limine responses are loaded in memory, which our OS can access.

Our initial code will be based off of limine-rust-template. We will only be targeting x86_64.

Get Limine

We need two types of compiled files from Limine:

- Files that are needed to boot Limine (including

BOOTX64.EFI) - The actual

limineexecutable, which we run on our host operating system (the operating system that you are writing the Rust code in)

If you're on NixOS, you will already have Limine from flake.nix. If you're not on NixOS, you can download / install it with Limine's instructions. Once you have the files, make sure that the environmental variable LIMINE_PATH is set to the folder containing BOOTX64.EFI, and the limine executable is in your PATH.

The rust-toolchain.toml file

Writing an operating system in Rust requires using nightly features, so we will specify a nightly toolchain. So create a rust-toolchain.toml file:

[toolchain]

channel = "nightly-2025-05-31"

components = ["rust-src"]

Configuring Limine

Create a file kernel/limine.conf. Leave it empty for now. We will use it to configure Limine later.

The Cargo workspace

We will have two Rust projects: the kernel, which is our actual operating system, and the runner, which will have programs that run our operating system in a virtual machine. For now, we'll just have the runner, and make the kernel in the next part.

Create a file Cargo.toml:

[workspace]

resolver = "3"

members = ["runner"]

Then create runner/Cargo.toml:

[package]

name = "runner"

version = "0.1.0"

edition = "2024"

publish = false

build.rs

Our runner will have two Rust programs. main.rs, which launches the virtual machine, and build.rs, which builds the .iso file which can be used to run our OS (in a virtual machine or on a real computer). Create runner/build.rs:

fn main() { }

Cargo will run this file before running main.rs.

We start by reading some env vars:

// This is the folder where a build script (this file) should place its output

let out_dir = PathBuf::from(env::var("OUT_DIR").unwrap());

// This is the `runner` folder

let runner_dir = PathBuf::from(env::var("CARGO_MANIFEST_DIR").unwrap());

// This folder contains Limine files such as `BOOTX64.EFI`

let limine_dir = PathBuf::from(env::var("LIMINE_PATH").unwrap());

To create the ISO, we will first create a folder which we want to be the root of the ISO, and then use xorriso to create the ISO (make sure you have xorriso installed).

We want this folder structure:

iso_root/

├── limine.conf

├── boot

│ └── limine

│ ├── limine-bios-cd.bin

│ ├── limine-bios.sys

│ └── limine-uefi-cd.bin

└── EFI

└── BOOT

├── BOOTIA32.EFI

└── BOOTX64.EFI

The following code copies files to achieve this:

// We will create an ISO file for our OS

// First we create a folder which will be used to generate the ISO

// We will use symlinks instead of copying to avoid unnecessary disk space used

let iso_dir = out_dir.join("iso_root");

create_dir_all(&iso_dir).unwrap();

// Limine config will be in `limine.conf`

let limine_conf = iso_dir.join("limine.conf");

ensure_symlink(runner_dir.join("limine.conf"), limine_conf).unwrap();

let boot_dir = iso_dir.join("boot");

create_dir_all(&boot_dir).unwrap();

// Copy files from the Limine packaeg into `boot/limine`

let out_limine_dir = boot_dir.join("limine");

create_dir_all(&out_limine_dir).unwrap();

for path in [

"limine-bios.sys",

"limine-bios-cd.bin",

"limine-uefi-cd.bin",

] {

let from = limine_dir.join(path);

let to = out_limine_dir.join(path);

ensure_symlink(from, to).unwrap();

}

// EFI/BOOT/BOOTX64.EFI is the executable loaded by UEFI firmware

// We will also copy BOOTIA32.EFI because xorisso will complain if it's not there

let efi_boot_dir = iso_dir.join("EFI/BOOT");

create_dir_all(&efi_boot_dir).unwrap();

for efi_file in ["BOOTX64.EFI", "BOOTIA32.EFI"] {

ensure_symlink(limine_dir.join(efi_file), efi_boot_dir.join(efi_file)).unwrap();

}

With the helper function:

pub fn ensure_symlink<P: AsRef<Path>, Q: AsRef<Path>>(original: P, link: Q) -> io::Result<()> {

match remove_file(&link) {

Ok(()) => Ok(()),

Err(error) => match error.kind() {

ErrorKind::NotFound => Ok(()),

_ => Err(error),

},

}?;

symlink(original, link)?;

Ok(())

}

Next, we use xorriso to create an ISO:

// We'll call the output iso `os.iso`

let output_iso = out_dir.join("os.iso");

// This command creates an ISO file from our `iso_root` folder.

// Symlinks will be read (the contents will be copied into the ISO file)

let status = std::process::Command::new("xorriso")

.arg("-as")

.arg("mkisofs")

.arg("--follow-links")

.arg("-b")

.arg(

out_limine_dir

.join("limine-bios-cd.bin")

.strip_prefix(&iso_dir)

.unwrap(),

)

.arg("-no-emul-boot")

.arg("-boot-load-size")

.arg("4")

.arg("-boot-info-table")

.arg("--efi-boot")

.arg(

out_limine_dir

.join("limine-uefi-cd.bin")

.strip_prefix(&iso_dir)

.unwrap(),

)

.arg("-efi-boot-part")

.arg("--efi-boot-image")

.arg("--protective-msdos-label")

.arg(iso_dir)

.arg("-o")

.arg(&output_iso)

.stderr(Stdio::inherit())

.stdout(Stdio::inherit())

.status()

.unwrap();

assert!(status.success());

Then we use the limine program to modify the ISO to work as a a hybrid ISO that boots on both BIOS and UEFI:

// This is needed to create a hybrid ISO that boots on both BIOS and UEFI. See https://github.com/limine-bootloader/limine/blob/v9.x/USAGE.md#biosuefi-hybrid-iso-creation

let status = std::process::Command::new("limine")

.arg("bios-install")

.arg(&output_iso)

.stderr(Stdio::inherit())

.stdout(Stdio::inherit())

.status()

.unwrap();

assert!(status.success());

Now our build.rs will create a os.iso file! The location of this file is not fixed, and is decided by Cargo. To pass the ISO's path to main.rs, we add:

let output_iso = output_iso.display();

println!("cargo:rustc-env=ISO={output_iso}");

main.rs

Let's start out with checking that ISO gets set:

let iso = env::var("ISO").unwrap();

println!("ISO path: {iso:?}");

Then run

cargo run

Example output:

ISO path: "/home/rajas/Documents/rust-os-tutorial/part-0/target/debug/build/runner-d62dee2feeec9cbb/out/os.iso"

Let's run qemu!

let ovmf = env::var("OVMF_PATH").unwrap();

// Qemu runs our OS in a virtual

let mut qemu = Command::new("qemu-system-x86_64");

// Specify the path to the ISO

qemu.arg("-cdrom");

qemu.arg(env!("ISO"));

// For UEFI on qemu, the path to OVMF.fd is needed

qemu.arg("-bios").arg(ovmf);

// Pass any args to qemu

env::args().skip(1).for_each(|arg| {

qemu.arg(arg);

});

let exit_status = qemu.status().unwrap();

process::exit(exit_status.code().unwrap_or(1));

Make sure that OVMF_PATH points to OVMF.fd. It's needed for UEFI on qemu.

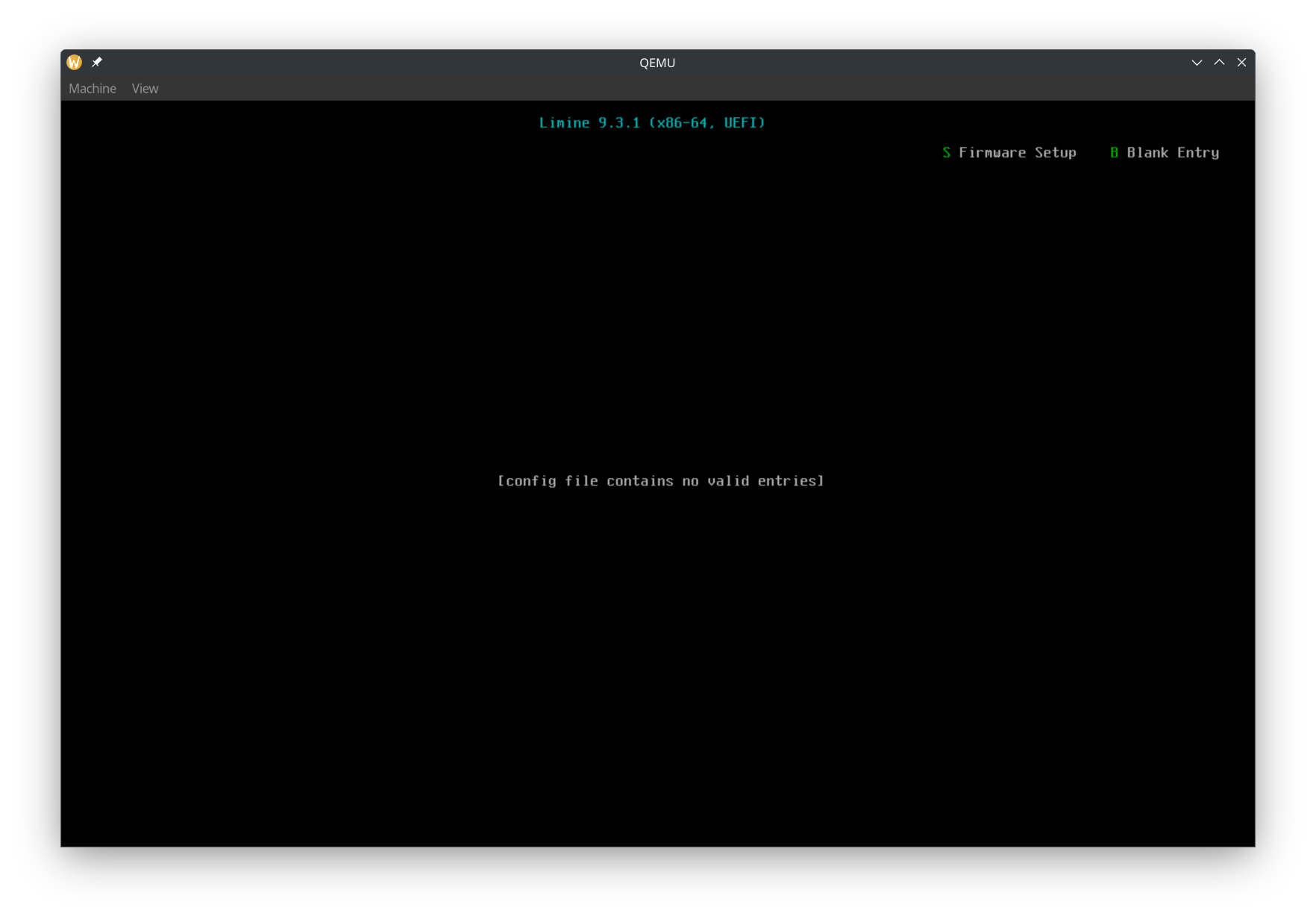

Now you should see the Limine menu!

Booting our kernel with Limine

We now have a runner which launches Limine in a VM. Now let's write the kernel that will get booted by Limine.

The x86_64-unknown-none target

In Rust, targets basically are what we are compiling for. Are we compiling it as a program that can run in Linux? A program that can run in Windows? A program to run in the web with WebAssembly? For our kernel, we are targeting bare metal on x86_64, so we need the x86_64-unknown-none target. In rust-toolchain.toml, add

targets = ["x86_64-unknown-none"]

Creating package kernel

Let's set the following properties in Cargo.toml

members = ["runner", "kernel"]

default-members = ["runner"]

default-members = ["runner"]

tells cargo that when we run cargo run, we want to run the binary in the runner project.

Create a file kernel/Cargo.toml:

[package]

name = "kernel"

version = "0.1.0"

edition = "2024"

publish = false

[dependencies]

limine = "0.4"

x86_64 = "0.15.2"

[[bin]]

name = "kernel"

test = false

bench = false

Here we have two dependencies. limine is the Rust library to declare Limine requests and read responses. x86_64 contains many useful functions for bare metal x86_64 programming.

main.rs

Now it's time to actually write the operating system's code! Create a file kernel/src/main.rs. In the top, add

#![no_std]

#![no_main]

This tells rust to not use the std part of the standard library and to not have a normal main function.

Next it's time for the special data to be read by Limine, as mentioned earlier:

/// Sets the base revision to the latest revision supported by the crate.

/// See specification for further info.

/// Be sure to mark all limine requests with #[used], otherwise they may be removed by the compiler.

#[used]

// The .requests section allows limine to find the requests faster and more safely.

#[unsafe(link_section = ".requests")]

static BASE_REVISION: BaseRevision = BaseRevision::new();

/// Define the stand and end markers for Limine requests.

#[used]

#[unsafe(link_section = ".requests_start_marker")]

static _START_MARKER: RequestsStartMarker = RequestsStartMarker::new();

#[used]

#[unsafe(link_section = ".requests_end_marker")]

static _END_MARKER: RequestsEndMarker = RequestsEndMarker::new();

Don't worry about understanding the details of the code. What you need to know is that the link_sections place the static variables in a location that Limine reads, and the above code has 1 request, which is the base revision request. This request is to tell Limine what version of the Limine protocol we want.

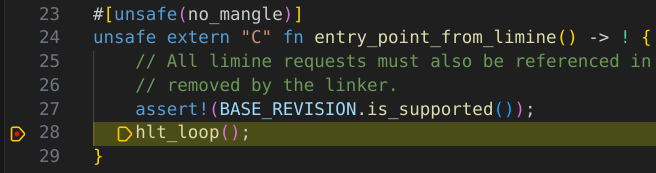

Next we write our entry point function

#[unsafe(no_mangle)]

unsafe extern "C" fn entry_point_from_limine() -> ! {

// All limine requests must also be referenced in a called function, otherwise they may be

// removed by the linker.

assert!(BASE_REVISION.is_supported());

hlt_loop();

}

The #[unsafe(no_mangle)] makes sure that the compiler doesn't rename the entry_point_from_limine function to something else, since we need the entry point function to have a consistent name.

We mark the function as unsafe to reduce the chance of accidentally calling our main function from our own code.

We use extern "C" because Limine will call our function using the C calling convention.

First we check BASE_REVISION and make sure that it was set to 0 using the is_supported function. This way, we know that Limine booted our kernel using the protocol version that we expect. Also, if we do not reference the BASE_REVISION variable, the compiler might remove the Limine request, causing Limine to not boot our OS correctly.

Next, we do nothing. Instead of using loop {} to do nothing, we use call hlt_loop:

fn hlt_loop() -> ! {

loop {

x86_64::instructions::hlt();

}

}

We do the hlt instruction to tell the CPU to stop. The CPU isn't guaranteed to stop forever, and it might resume doing stuff and execute the next instruction. That's why we have a forever loop in which we call hlt.

But we also have to add a panic handler:

#[panic_handler]

fn rust_panic(_info: &core::panic::PanicInfo) -> ! {

hlt_loop();

}

When using std, Rust already includes a panic handler which prints a nice message. However, since we are writing Rust for bare metal, we need to specify a function which gets called if our kernel panics. Later, we can also print a pretty message with the panic error, but for now, we just call hlt_loop.

Linker File

To make our kernel's executable file compatible with Limine, we need to add a linker file (kernel/linker-x86_64.ld). An important part to note is ENTRY(entry_point_from_limine), where entry_point_from_limine is referencing the entry_point_from_limine function in our code. If you want, you can call the entry point function something else, such as kernel_main or kmain, as long as you update the function in main.rs as well as the linker file.

To tell Cargo to use our linker file, create kernel/build.rs:

use std::path::PathBuf;

fn main() {

let arch = std::env::var("CARGO_CFG_TARGET_ARCH").unwrap();

let dir = std::env::var("CARGO_MANIFEST_DIR").unwrap();

let linker_file = PathBuf::from(dir).join(format!("linker-{arch}.ld"));

let linker_file = linker_file.to_str().unwrap();

// Tell cargo to pass the linker script to the linker..

println!("cargo:rustc-link-arg=-T{linker_file}");

// ..and to re-run if it changes.

println!("cargo:rerun-if-changed={linker_file}");

}

.cargo/config.toml

We also need to pass an option to rustc. Create .cargo/config.toml:

[target.x86_64-unknown-none]

rustflags = ["-C", "relocation-model=static"]

Without a static ELF relocation model, Limine will not boot our kernel.

Building

At this point, we should be able to build the kernel:

cargo build --package kernel --target x86_64-unknown-none

Putting the kernel in our ISO

We want the build process to be like this:

- Build the kernel

- Create the ISO

- Run the ISO in qemu

We need the runner/build.rs to have the output binary from the kernel package. Cargo has a (experimental) feature that lets us do that. First, let's enable the feature by adding this to the top of .cargo/config.toml:

[unstable]

# enable the unstable artifact-dependencies feature, see

# https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/cargo/reference/unstable.html#artifact-dependencies

bindeps = true

Next, let's tell Rust that the runner/build.rs depends on the output binary from the kernel package. Add this to runner/Cargo.toml:

[build-dependencies]

kernel = { path = "../kernel", artifact = "bin", target = "x86_64-unknown-none" }

Now we can add this to runner/build.rs:

// Cargo passes us the path the to kernel executable because it is an artifact dep

let kernel_executable_file = env::var("CARGO_BIN_FILE_KERNEL").unwrap();

Cargo will build the kernel first before building the runner.

Let's put our kernel as kernel:

// Symlink the kernel binary to `kernel`

let kernel_dest = iso_dir.join("kernel");

ensure_symlink(&kernel_executable_file, &kernel_dest).unwrap();

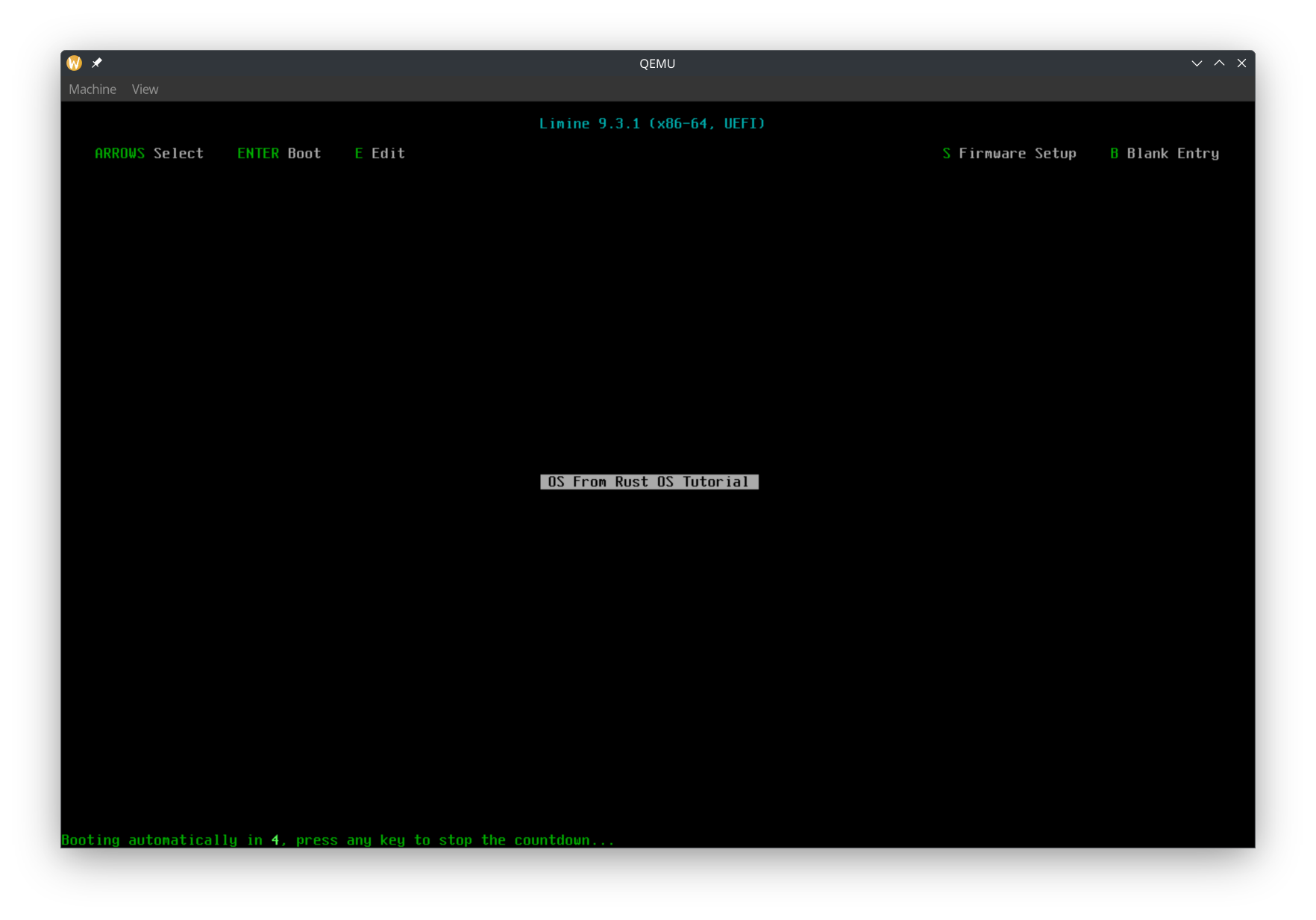

Updating Limine config

We put our kernel in kernel, now we need to tell Limine to add a boot option to boot it. Update runner/limine.conf:

# The entry name that will be displayed in the boot menu.

/OS From Rust OS Tutorial

protocol: limine

kernel_path: boot():/kernel

Note that we specify the limine protocol. The Limine bootloader can also boot with other protocols, but we want the Limine protocol.

In action

Now let's run it again! Now QEMU will show our boot option, and you can boot our kernel!

Debugging with GDB

We now made it so that there is a black screen after Limine boots our kernel. But... is our kernel working? Did it check the Limine version and enter the hlt_loop?

Let's debug our kernel to find out!

cargo r -- -s -S

The -s tells QEMU to start a GDB debug server at port 1234. The -S tells QEMU to immediately pause the VM (so that we can attach the debugger before our code runs).

Now, we need to find the path to the kernel binary. Looking at the output from the runner, our iso is at <something>/out/os.iso. We can get the path to the kernel at <something>/out/iso_root/kernel.

Make sure you have gdb installed. Run gdb <kernel_file_path>. In my case, it is:

gdb /home/rajas/Documents/rust-os-tutorial/part-1/target/debug/build/runner-f2245a6f9dda311c/out/iso_root/kernel

Then inside GDB, run target remote :1234. It should look something like this:

Remote debugging using :1234

0x000000000000fff0 in ?? ()

Now we can set a breakpoint at hlt_loop like this:

(gdb) break main.rs:36

Breakpoint 1 at 0xffffffff80000051: file kernel/src/main.rs, line 37.

Now let's unpause the VM with the continue GDB command.

(gdb) continue

Continuing.

Breakpoint 1, kernel::hlt_loop () at kernel/src/main.rs:37

37 loop {

The Limine menu should appear, and when Limine boots our kernel, we'll reach the breakpoint. So we know it's working!

Debugging with Vscodium

With Vscodium (or Vscode), you can easily debug our OS. No need to manually run GDB commands.

Extension Required

Get the "CodeLLDB" extension.

launch.json

Then create the file .vscode/launch.json:

{

// Use IntelliSense to learn about possible attributes.

// Hover to view descriptions of existing attributes.

// For more information, visit: https://go.microsoft.com/fwlink/?linkid=830387

"version": "0.2.0",

"configurations": [

{

"name": "Debug kernel in QEMU",

"type": "lldb",

"request": "launch",

"targetCreateCommands": [

"target create ${workspaceFolder}/target/debug/build/runner-f2245a6f9dda311c/out/iso_root/kernel",

],

"processCreateCommands": [

"gdb-remote localhost:1234",

],

},

],

}

Replace the path to the kernel with your own.

Now let's try it. Run

cargo run -- -s -S

And then in Vscodium, do "Run and Debug". It should be paused, since we passed the -S flag to QEMU. At this point, try setting a breakpoint. I will set a breakpoint in the hlt_loop(); line in entry_point_from_limine. Then click continue in the debug tools. Once Limine boots the kernel, it should reach the breakpoint.

Much easier than using the

Much easier than using the gdb command manually!

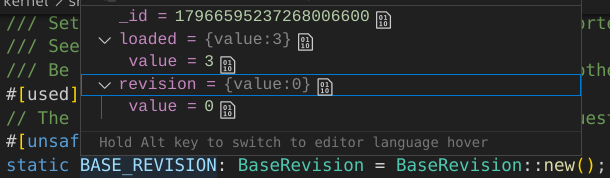

We can also nicely view the values of variables. We don't have any local variables, but you can add some to try it. We can also see the values of global variables.

You can verify that

You can verify that BASE_REVISION has a loaded value of 3 and revision value of 0. The revision being 0 indicates that Limine successfully processed our base revision request. The loaded value of 3 indicates that our kernel was loaded with version 3 of the Limine protocol (which is the version we want).

Out dir symlink

One inconvenient thing is that the kernel path is not constant (it could change whenever Cargo feels like it). We can workaround that by creating a symlink in build.rs which makes runner/out_dir point to the out_dir, where we create the iso_root folder and os.iso:

// Symlink the out dir so we get a constant path to it

ensure_symlink(&out_dir, runner_dir.join("out_dir")).unwrap();

Also add runner/out_dir to .gitignore. Then change the target create command to target create ${workspaceFolder}/runner/out_dir/iso_root/kernel.

Automating cargo run

Create a .vscode/tasks.json file:

{

"version": "2.0.0",

"tasks": [

{

"type": "cargo",

"command": "run",

"args": [

"--",

"-s",

"-S",

],

"problemMatcher": [

"$rustc",

],

"label": "Start QEMU with GDB Debugging",

"isBackground": true,

"runOptions": {

// You can't have multiple processes listening on port 1234 at the same time

"instanceLimit": 1,

},

},

],

}

And in our debugging config in launch.json, add

"preLaunchTask": "Start QEMU with GDB Debugging",

Now we can just click / use a keyboard shortcut, and QEMU and the debugger will start.

Speeding up the debugging process

Add

timeout: 0

to the top of limine.conf. We don't need to interact with Limine. We just want it to boot our kernel.

Also, add

"continue",

to the processCreateCommands in launch.json. That way as soon as the debugger connects the VM will continue executing.

Hello World!

Now it's time to print "Hello World!" in our kernel. Normally, we would use the println macro. But since we are in no_std, there is no println macro. We can print to the COM1 serial port instead. More info: https://os.phil-opp.com/testing/#serial-port. Serial ports let us read and write data. Most modern computers don't have serial ports, but QEMU does. We can access COM1 through x86 I/O ports (also see https://wiki.osdev.org/Port_IO). We can read and write to I/O ports using in and out instructions.

Let's use the uart_16550 crate. In kernel/Cargo.toml dependencies, add

uart_16550 = "0.3.2"

In kernel/main.rs, add

use uart_16550::SerialPort;

and

use core::fmt::Write;

Then we can write to COM1 using

let mut serial_port = unsafe { SerialPort::new(0x3F8) };

serial_port.init();

writeln!(serial_port, "Hello World!\r").unwrap();

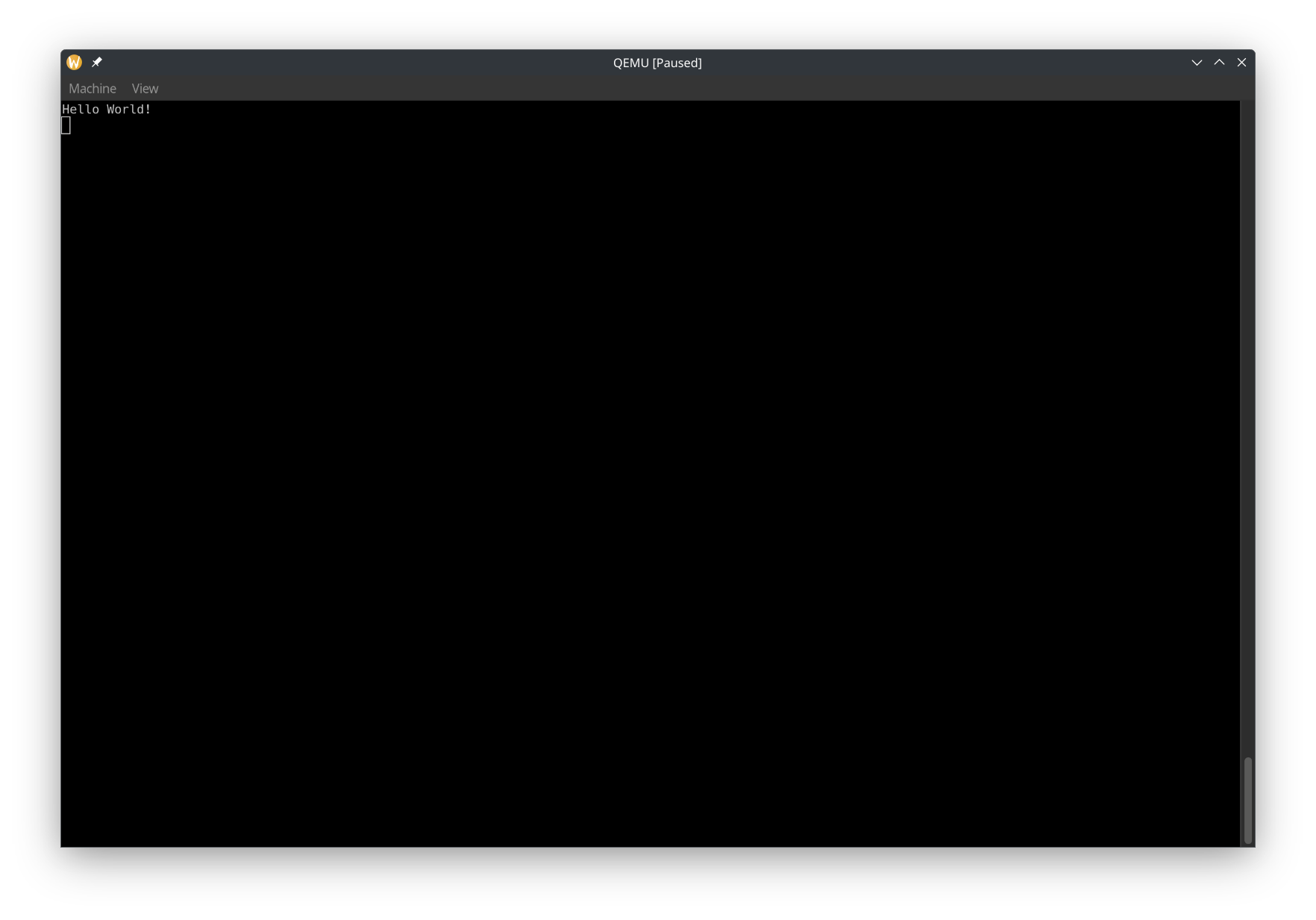

Now run it, and in the QEMU window, select View -> serial0. It should look like this:

We can make QEMU not create a window and print COM1 to the terminal by using --nographic. Let's also update tasks.json. Note that when you specify --nographic, you can't close QEMU with Ctrl + C and instead have to use Ctrl + A and then press X.

Drawing to the Screen

Most likely, you will not be able to read from COM1 on if you run the OS on a real computer, or use a debugger on it. So let's draw to the screen to make sure that our OS works on real machines!

To draw to the screen, we will be writing to a region of memory which is memory mapped to a frame buffer. A frame buffer basically represents the pixels on the screen. You typically put a dot on the screen by writing the pixel's RGB values to the region in the frame buffer corresponding to that pixel. Limine makes it easy for us to get a frame buffer. Let's add the Limine request. Before we add the request, let's move all of the Limine-related stuff to it's own module, limine_requests.rs. Then let's create the request:

#[used]

#[unsafe(link_section = ".requests")]

pub static FRAME_BUFFER_REQUEST: FramebufferRequest = FramebufferRequest::new();

To draw shapes, text, and more, we'll use the embedded-graphics crate. Add it to kernel/Cargo.toml:

embedded-graphics = "0.8.1"

Next, let's make a struct for drawing a pixel using the Limine-provided pixel info. Create rgb_pixel_info.rs:

use embedded_graphics::{pixelcolor::Rgb888, prelude::RgbColor};

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy)]

pub struct RgbPixelInfo {

pub red_mask_size: u8,

pub red_mask_shift: u8,

pub green_mask_size: u8,

pub green_mask_shift: u8,

pub blue_mask_size: u8,

pub blue_mask_shift: u8,

}

impl RgbPixelInfo {

/// Technically, Limine and this struct could have a pixel size other than u32, in which case you shouldn't use this method

pub fn build_pixel(&self, color: Rgb888) -> u32 {

let mut n = 0;

n |= ((color.r() as u32) & ((1 << self.red_mask_size) - 1)) << self.red_mask_shift;

n |= ((color.g() as u32) & ((1 << self.green_mask_size) - 1)) << self.green_mask_shift;

n |= ((color.b() as u32) & ((1 << self.blue_mask_size) - 1)) << self.blue_mask_shift;

n

}

}

And also a struct that contains the information from Limine. frame_buffer_info.rs:

use crate::RgbPixelInfo;

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy)]

#[non_exhaustive]

pub struct FrameBufferInfo {

pub width: u64,

pub height: u64,

pub pitch: u64,

pub bits_per_pixel: u16,

pub pixel_info: RgbPixelInfo,

}

impl From<&limine::framebuffer::Framebuffer<'_>> for FrameBufferInfo {

fn from(framebuffer: &limine::framebuffer::Framebuffer) -> Self {

FrameBufferInfo {

width: framebuffer.width(),

height: framebuffer.height(),

pitch: framebuffer.pitch(),

bits_per_pixel: framebuffer.bpp(),

pixel_info: RgbPixelInfo {

red_mask_size: framebuffer.red_mask_size(),

red_mask_shift: framebuffer.red_mask_shift(),

green_mask_size: framebuffer.green_mask_size(),

green_mask_shift: framebuffer.green_mask_shift(),

blue_mask_size: framebuffer.blue_mask_size(),

blue_mask_shift: framebuffer.blue_mask_shift(),

},

}

}

}

Then create a new file, frame_buffer_embedded_graphics.rs. Let's create a wrapper struct that will implement DrawTarget, which let's us draw to it with embedded-graphics.

pub struct FrameBufferEmbeddedGraphics<'a> {

buffer: &'a mut [u32],

info: FrameBufferInfo,

pixel_pitch: usize,

bounding_box: Rectangle,

}

impl FrameBufferEmbeddedGraphics<'_> {

/// # Safety

/// The frame buffer must be mapped at `addr`

pub unsafe fn new(addr: NonZero<usize>, info: FrameBufferInfo) -> Self {

if info.bits_per_pixel as u32 == u32::BITS {

Self {

buffer: {

let mut ptr = NonNull::new(slice_from_raw_parts_mut(

addr.get() as *mut u32,

(info.pitch * info.height) as usize / size_of::<u32>(),

))

.unwrap();

// Safety: This memory is mapped

unsafe { ptr.as_mut() }

},

info,

pixel_pitch: info.pitch as usize / size_of::<u32>(),

bounding_box: Rectangle {

top_left: Point::zero(),

size: Size {

width: info.width.try_into().unwrap(),

height: info.height.try_into().unwrap(),

},

},

}

} else {

panic!("DrawTarget implemented for RGB888, but bpp doesn't match RGB888");

}

}

}

In the new function, we make sure that the bytes per pixel is 4 (R, G, B, and an unused byte). This is because in our drawing logic, we will store each pixel as a u32.

Now let's implement the Dimensions trait, which is needed for DrawTarget:

impl Dimensions for FrameBufferEmbeddedGraphics<'_> {

fn bounding_box(&self) -> embedded_graphics::primitives::Rectangle {

self.bounding_box

}

}

Now let's implement the DrawTarget trait:

impl DrawTarget for FrameBufferEmbeddedGraphics<'_> {

type Color = Rgb888;

type Error = Infallible;

fn draw_iter<I>(&mut self, pixels: I) -> Result<(), Self::Error>

where

I: IntoIterator<Item = embedded_graphics::Pixel<Self::Color>>,

{

let bounding_box = self.bounding_box();

pixels

.into_iter()

.filter(|Pixel(point, _)| bounding_box.contains(*point))

.for_each(|Pixel(point, color)| {

let pixel_index = point.y as usize * self.pixel_pitch + point.x as usize;

self.buffer[pixel_index] = self.info.pixel_info.build_pixel(color);

});

Ok(())

}

}

Now in main.rs, let's use embedded graphics to draw to the screen:

let frame_buffer = FRAME_BUFFER_REQUEST.get_response().unwrap();

if let Some(frame_buffer) = frame_buffer.framebuffers().next() {

let mut frame_buffer = {

let addr = frame_buffer.addr().addr().try_into().unwrap();

let info = (&frame_buffer).into();

unsafe { FrameBufferEmbeddedGraphics::new(addr, info) }

};

frame_buffer.clear(Rgb888::MAGENTA).unwrap();

}

Limine gives us a slice of frame buffers, but here we only draw to the first frame buffer, if it exists.

Depending on your host computer, you might notice that this is pretty slow. Let's implement fill_solid so that embedded_graphics can draw certain shapes, such as rectangles, much faster:

fn fill_solid(&mut self, area: &Rectangle, color: Self::Color) -> Result<(), Self::Error> {

let area = area.intersection(&self.bounding_box);

let pixel = self.info.pixel_info.build_pixel(color);

let width = area.size.width as usize;

let top_left_x = area.top_left.x as usize;

for y in area.top_left.y as usize..area.top_left.y as usize + area.size.height as usize {

let pixel_index = y * self.pixel_pitch + top_left_x;

let pixels = &mut self.buffer[pixel_index..pixel_index + width];

pixels.fill(pixel);

}

Ok(())

}

Now when we fill the screen, it should draw much faster.

Learn more

Running on real hardware

Now that we draw something on the screen, we can see our OS in action on real computers. It should work on any x86_64 computer with UEFI or legacy BIOS.

Writing the ISO to a disk

We can write our file at runner/out_dir/iso_root/os.iso to a disk in any way we want. Some tools are:

If you know what you are doing, you can use dd instead. You can also use Ventoy, but it might not work on really old computers.

Booting the OS

Plug in your disk (most likely you are using a USB disk, so just plug it in). When turning on your computer, you have to press a certain key to enter the boot device selection menu. On the old Lenovo computer with Legacy BIOS that I'm using, this key is F12. On Chromebooks running MrChromebox firmware (UEFI), you can press Esc or Arrow Down. Then choose the USB disk containing your OS. If you don't know what this key is, you can usually just look it up online and you'll find the key based on the computer's brand.

You should see the entire screen turn magenta!

Here is a picture of it on a Jinlon, a Chromebook with UEFI.

And here is a picture of it on an old Lenovo computer with Legacy BIOS.

Limine makes it easy to draw to the screen regardless of the firmware type. Limine handles the process of getting the frame buffer, which is different on UEFI than on legacy BIOS.

Logging

The log crate

As we expand our kernel, it will be very useful to be able to log messages. The log crate provides macros similar to println, and works on no_std because you have to write your own log function implementation. Add this to the kernel deps:

log = "0.4.27"

Then create a new file called logger.rs. We will be logging to two places: the serial port (COM1), and the screen (if available). Let's start with creating an empty struct which will implement the Log trait:

use log::Log;

use uart_16550::SerialPort;

struct KernelLogger {}

impl Log for KernelLogger {

fn enabled(&self, _metadata: &log::Metadata) -> bool {

todo!()

}

fn log(&self, record: &log::Record) {

todo!()

}

fn flush(&self) {

todo!()

}

}

Spin lock

We have to implement the log function, but we are only given an &self function. We need to put SerialPort in something which has interior mutability. We can use a mutex to achieve this. Normally, we would use the Mutex from std. In no_std, we can use the spin crate for a simple mutex. It works by continuously checking in a loop if the mutex is available.

spin = "0.10.0"

We can create a struct Inner which will store the mutable data, and put it in a spin lock:

struct Inner {}

struct KernelLogger {

inner: spin::Mutex<Inner>,

}

Colors

Now let's start writing the actual logging functions. We will be making our logger colorful. The way you print colored text is different on the serial port vs the screen. On the serial port we will use ANSI escape codes, which involve an escape code before and after the string we want to color. On the screen, we specify the color when drawing text using embedded-graphics. Let's create an enum for the colors we will be using:

/// Represents a color in a terminal or screen. The default color may depend on if the theme is light or dark.

enum Color {

Default,

BrightRed,

BrightYellow,

BrightBlue,

BrightCyan,

BrightMagenta,

}

Now let's create a function that let's us write colored text on both log outputs:

impl Inner {

fn write_with_color(&mut self, color: Color, string: impl Display) {}

}

And then we can call the function in the Log implementation:

fn log(&self, record: &log::Record) {

let mut inner = self.inner.try_lock().unwrap();

let level = record.level();

inner.write_with_color(

match level {

Level::Error => Color::BrightRed,

Level::Warn => Color::BrightYellow,

Level::Info => Color::BrightBlue,

Level::Debug => Color::BrightCyan,

Level::Trace => Color::BrightMagenta,

},

format_args!("{level:5} "),

);

inner.write_with_color(Color::Default, record.args());

inner.write_with_color(Color::Default, "\n");

}

Mutexes can feel like an easy way to safety get a &mut to a global variable, but whenever we use mutexes we have to keep in mind the possibility of a deadlock. This is why we use .try_lock().unwrap() instead of .lock(), so that we panic by default if the lock is busy, so we know for sure there won't be a deadlock.

Writing to serial

Now let's implement the actual writing to serial inside write_with_color. To Inner, add:

serial_port: SerialPort

We'll use owo_colors to handle the ANSI escape codes for us.

owo-colors = "4.2.1"

We also need to convert LF to CRLF, so that the serial output looks as expected inside QEMU's serial0 view. Doing this is simple with the core::fmt::Write trait. Create writer_with_cr.rs:

use core::fmt::Write;

use unicode_segmentation::UnicodeSegmentation;

/// A writer that writes to a writer, replacing `\n` with `\r\n`

pub struct WriterWithCr<T> {

writer: T,

}

impl<T> WriterWithCr<T> {

pub const fn new(writer: T) -> Self {

Self { writer }

}

}

impl<T: Write> Write for WriterWithCr<T> {

fn write_str(&mut self, s: &str) -> core::fmt::Result {

for c in s.graphemes(true) {

match c {

"\n" => self.writer.write_str("\r\n")?,

s => self.writer.write_str(s)?,

}

}

Ok(())

}

}

And then in write_with_color:

// Write to serial

{

let string: &dyn Display = match color {

Color::Default => &string,

Color::BrightRed => &string.bright_red(),

Color::BrightYellow => &string.bright_yellow(),

Color::BrightBlue => &string.bright_blue(),

Color::BrightCyan => &string.bright_cyan(),

Color::BrightMagenta => &string.bright_magenta(),

};

let mut writer = WriterWithCr::new(&mut self.serial_port);

write!(writer, "{string}").unwrap();

}

Writing to the screen

We'll need a FrameBufferEmbeddedGraphics, and we'll also need to keep track of the cursor position. Create a struct:

struct DisplayData {

display: FrameBufferEmbeddedGraphics<'static>,

position: Point,

}

and then add it to Inner:

display: Option<DisplayData>,

We use Option because there will not always be a screen.

Then, inside write_with_color, add

// Write to screen

if let Some(display_data) = &mut self.display { }

Now there is a slightly tricky part. We are given an impl Display, but we need to process the text character by character. The only way to do that is to implement the Write trait. So let's create a temporary struct that implements the Write trait:

struct Writer<'a> {

display: &'a mut FrameBufferEmbeddedGraphics<'static>,

position: &'a mut Point,

text_color: <FrameBufferEmbeddedGraphics<'a> as DrawTarget>::Color,

}

When we run out of vertical space on the screen, we'll shift everything that's on the screen up, so that we can see the new text as well as part of the old text. To do this, let's implement a shift_up method:

impl FrameBufferEmbeddedGraphics<'_> {

/// Moves everything on the screen up, leaving the bottom the same as it was before

pub fn shift_up(&mut self, amount: usize) {

self.buffer.copy_within(amount * self.pixel_pitch.., 0);

}

}

To process the string character by character, we will use the unicode-segmentation crate's graphemes method.

unicode-segmentation = "1.12.0"

And then we can implement Write:

use embedded_graphics::mono_font::iso_8859_16::FONT_10X20;

impl Write for Writer<'_> {

fn write_str(&mut self, s: &str) -> core::fmt::Result {

let font = FONT_10X20;

let background_color = Rgb888::BLACK;

for c in s.graphemes(true) {

let height_not_seen = self.position.y + font.character_size.height as i32

- self.display.bounding_box().size.height as i32;

if height_not_seen > 0 {

self.display.shift_up(height_not_seen as usize);

self.position.y -= height_not_seen;

}

match c {

"\r" => {

// We do not handle special cursor movements

}

"\n" | "\r\n" => {

// Fill the remaining space with background color

Rectangle::new(

*self.position,

Size::new(

self.display.bounding_box().size.width

- self.position.x as u32,

font.character_size.height,

),

)

.into_styled(

PrimitiveStyleBuilder::new()

.fill_color(background_color)

.build(),

)

.draw(self.display)

.map_err(|_| core::fmt::Error)?;

self.position.y += font.character_size.height as i32;

self.position.x = 0;

}

c => {

let style = MonoTextStyleBuilder::new()

.font(&font)

.text_color(self.text_color)

.background_color(background_color)

.build();

*self.position =

Text::with_baseline(c, *self.position, style, Baseline::Top)

.draw(self.display)

.map_err(|_| core::fmt::Error)?;

if self.position.x as u32 + font.character_size.width

> self.display.bounding_box().size.width

{

self.position.y += font.character_size.height as i32;

self.position.x = 0;

}

}

}

}

Ok(())

}

}

And let's use our Writer:

let mut writer = Writer {

display: &mut display_data.display,

position: &mut display_data.position,

text_color: match color {

Color::Default => Rgb888::WHITE,

// Mimick the ANSI escape colors

Color::BrightRed => Rgb888::new(255, 85, 85),

Color::BrightYellow => Rgb888::new(255, 255, 85),

Color::BrightBlue => Rgb888::new(85, 85, 255),

Color::BrightCyan => Rgb888::new(85, 255, 255),

Color::BrightMagenta => Rgb888::new(255, 85, 255),

},

};

write!(writer, "{}", string).unwrap();

Now we're done implementing the Log trait!

Logger global variable

Now let's have a global variable for our logger and a function to initialize our logger.

static LOGGER: KernelLogger = KernelLogger {

inner: spin::Mutex::new(Inner {

serial_port: unsafe { SerialPort::new(0x3F8) },

display: None,

}),

};

pub fn init(frame_buffer: &'static FramebufferResponse) -> Result<(), log::SetLoggerError> {

let mut inner = LOGGER.inner.try_lock().unwrap();

inner.serial_port.init();

inner.display = frame_buffer

.framebuffers()

.next()

.map(|frame_buffer| DisplayData {

display: FrameBufferEmbeddedGraphics::new(frame_buffer),

position: Point::zero(),

});

log::set_max_level(LevelFilter::max());

log::set_logger(&LOGGER)

}

Note that the log crate requires us to set a level filter, which lets us choose to only log messages with a certain importance. For example, we can set the level filter to only log warn and error messages, and not log info, debug, or trace messages. You can try it out by setting the max level to LevelFilter::Warn. Then you will not see any messages from log::info.

Using the logger

Now we can log from main.rs like this:

let frame_buffer_response = FRAME_BUFFER_REQUEST.get_response().unwrap();

logger::init(frame_buffer_response).unwrap();

log::info!("Hello World!");

Remove the drawing the screen magenta code.

Logging panics

Now that we have a logger, let's update our panic handler:

#[panic_handler]

fn rust_panic(info: &core::panic::PanicInfo) -> ! {

log::error!("{info}");

hlt_loop();

}

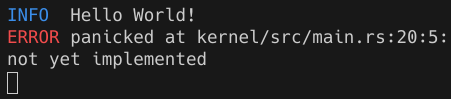

Results

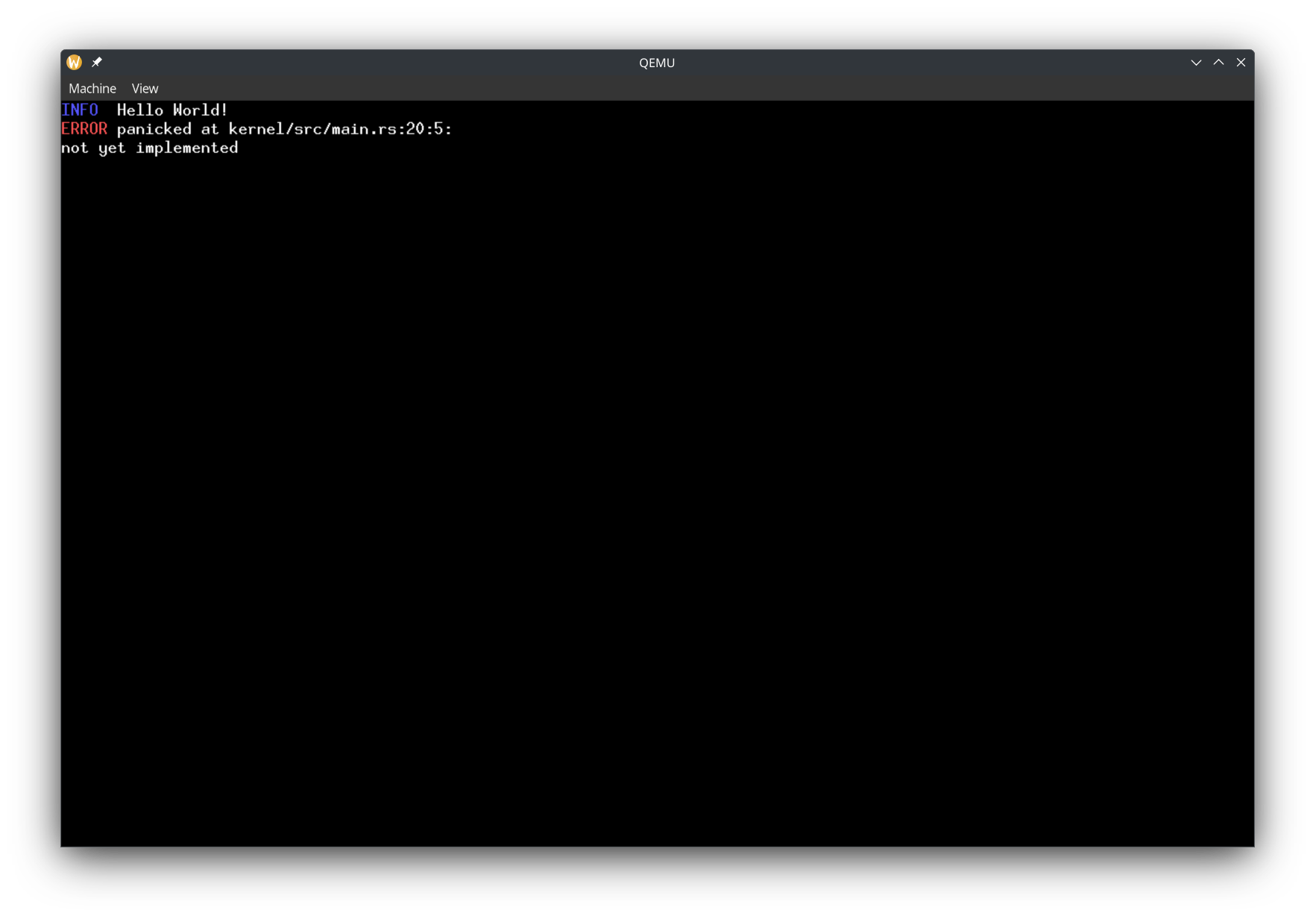

To check our panic handler, let's temporarily put todo!() before hlt_loop in our entry function. Now we should see

INFO Hello World!

ERROR panicked at kernel/src/main.rs:20:5:

not yet implemented

Which will look like this on a terminal:

And on a screen:

Using all CPUs

We are in a state where we have a function that gets executed on boot. We have a logger, and we can start doing stuff. But first, let's use 100% of our computer - and by that, I mean, all of the CPUs.

You might be thinking, don't most computers just have 1 CPU?. But from the kernel's perspective, every core in the CPU is like its own CPU. And actually, every thread in a CPU with hyper-threading cores counts as a CPU from the kernel's perspective. For example, on a laptop with the i7-10610U processor, looking at the specs, we would say it's a laptop with 1 CPU, with 4 cores and 8 threads. From the kernel's perspective, it's a computer with 8 CPUs.

Limine MP Request

Limine makes running code on all CPUs very easy. We just need to use Limine's MP request.

#[used]

#[unsafe(link_section = ".requests")]

pub static MP_REQUEST: MpRequest = MpRequest::new().with_flags(RequestFlags::X2APIC);

We use the X2APIC request flag. This tutorial will explain more about what that is in a later part. For now, you just need to know that this flag is needed for Limine to boot our kernel when there are >256 CPUs.

Up until now, our code has only been running on 1 CPU. This CPU is called the bootstrap processor (BSP). Let's change our hello world to say "Hello from BSP".

The other CPUs are called application processors (APs). Limine has already started the APs for us, and they are waiting to jump to a function.

Let's make a function for the APs:

unsafe extern "C" fn entry_point_from_limine_mp(_cpu: &limine::mp::Cpu) -> ! {

// log::info!("Hello from AP");

hlt_loop()

}

Using the MP request, we can run the function in all of the APs:

let mp_response = MP_REQUEST.get_response().unwrap();

for cpu in mp_response.cpus() {

cpu.goto_address.write(entry_point_from_limine_mp);

}

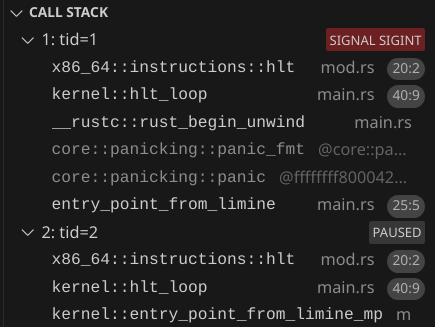

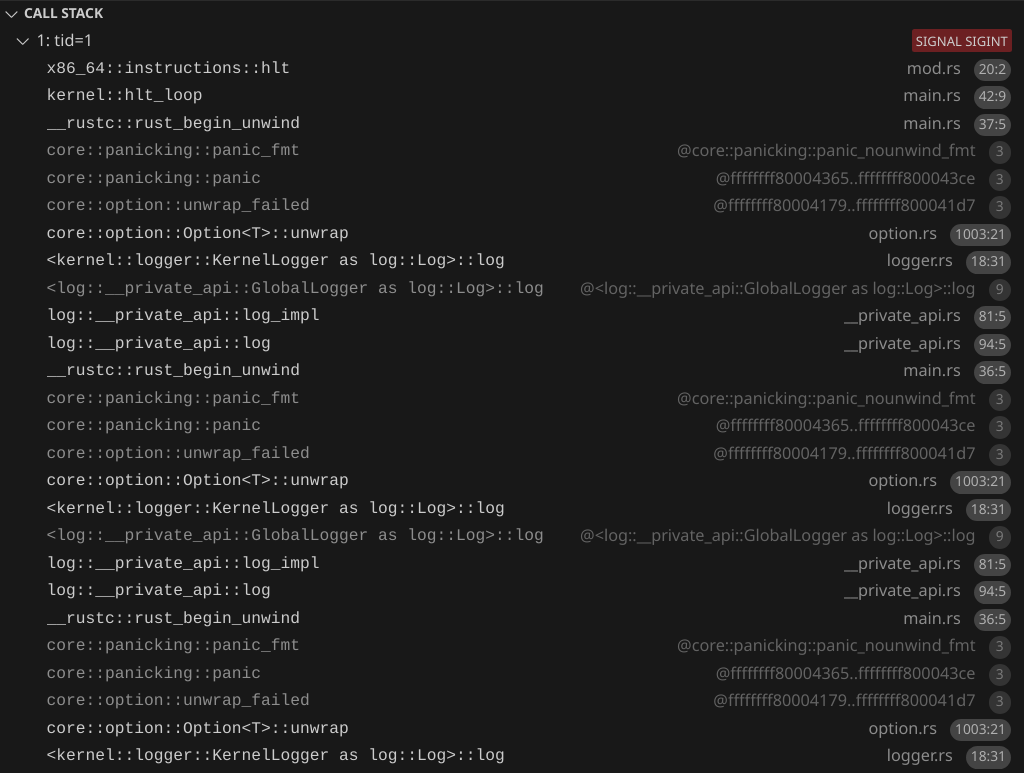

By default, QEMU only gives the VM 1 CPU. We can specify the number of CPUs using the --smp flag. Let's test it out by using --smp 2 and using the debugger to confirm that the other CPU does execute our function:

You might have to click pause on the debugger to view the call stack.

Infinite recursive panics!

But of course, we want to log something, not just look at it through the debugger. Notice how now we could have a situation where we try to access the serial port for logging from two or more different places at once. Our .try_lock().unwrap() could panic, since the logger could be locked by one CPU while a different CPU tries to access it.

And in the way our kernel is right now, we could cause a panic inside of our panic handler!

log::error!("{}", info);

And in fact, that does happen. Uncomment the "Hello from AP" and run it. The first CPU will be printing its panic message while the second CPU also tries to print at the same time, causing a panic because we .try_lock().unwrap(). We can see the recursive panic with the debugger:

Preventing recursive panics

We're going to change our logger so it doesn't panic, but before that, let's change our panic handler to avoid infinite recursive panics:

static DID_PANIC: AtomicBool = AtomicBool::new(false);

#[panic_handler]

fn rust_panic(info: &core::panic::PanicInfo) -> ! {

if !DID_PANIC.swap(true, Ordering::Relaxed) {

log::error!("{info}");

hlt_loop();

} else {

hlt_loop();

}

}

Let's also move our panic handler to a separate file, panic_handler.rs, and move hlt_loop to hlt_loop.rs. Now at most, we can have two panics. And the second panic is guaranteed not to cause further panics because the hlt_loop function cannot cause panics. This way, if we have another bug in the logger, we don't have recursive panics again.

Spinning to wait

Now let's replace self.inner.try_lock().unwrap() with self.inner.lock(). Now instead of panicking if the lock is held by something else, it will continuously check if the lock is free, until it becomes free. This will solve our problem, but again, be aware that if a deadlock happens, the CPU will just spin forever and it will be harder to debug than a panic.

Now we should see this (the order can vary depending on which CPU gets the lock first):

INFO Hello from BSP

INFO Hello from AP

And when running with --smp 8:

INFO Hello from BSP

INFO Hello from AP

INFO Hello from AP

INFO Hello from AP

INFO Hello from AP

INFO Hello from AP

INFO Hello from AP

INFO Hello from AP

Global Allocator

In x86_64 (and pretty much every architecture), there is physical memory and virtual memory. Physical memory is the actual RAM, and also memory-mapped I/O (one example is the HPET, which we will program later). Virtual memory is what our code references. Virtual memory is mapped to physical memory, and the mappings are programmed using page tables. See https://os.phil-opp.com/paging-introduction/ for a more in-depth explanation.

When we write Rust code in std, we have data types such as Box, Vec, Rc, and Arc. However, in no_std, we need an allocator to use those types. In no_std, there is no allocator included, and we need to provide our own. See https://os.phil-opp.com/allocator-designs/ for more detailed information about what allocators are.

An allocator basically has a pool of memory (think of it as a &mut [MaybeUninit<u8>]) which it allocates towards any data type used by any code. The allocator has to keep track of which parts of memory are allocated, and be able to allocate, deallocate, and (optional, but useful for performance) grow / shrink already allocated memory regions. We don't have to implement an allocator because there are many existing crates that do it for us. We will use the talc crate:

talc = "4.4.3"

To enable using alloc, we need to add in main.rs:

extern crate alloc;

Create a file memory.rs:

// This tells Rust that global allocations will use this static variable's allocation functions

// Talck is talc's allocator, but behind a lock, so that it can implement `GlobalAlloc`

// We tell talc to use a `spin::Mutex` as the locking method

// If talc runs out of memory, it runs an OOM (out of memory) handler.

// For now, we do not implement a method of allocating more memory for the global allocator, so we just error on OOM

#[global_allocator]

static GLOBAL_ALLOCATOR: Talck<spin::Mutex<()>, ErrOnOom> = Talck::new({

// Initially, there is no memory backing `Talc`. We will add memory at run time

Talc::new(ErrOnOom)

});

Finding physical memory

We need to find physical memory to use for our global allocator at run time. For this, we will use Limine's Memory Map feature:

#[used]

#[unsafe(link_section = ".requests")]

pub static MEMORY_MAP_REQUEST: MemoryMapRequest = MemoryMapRequest::new();

Let's create an init function in memory.rs:

/// Finds unused physical memory for the global allocator and initializes the global allocator.

/// Returns the start address of the physical memory used for the global allocator.

///

/// # Safety

/// This function must be called exactly once, and no page tables should be modified before calling this function.

pub unsafe fn init(memory_map: &'static MemoryMapResponse) {

let global_allocator_size = {

// 4 MiB

4 * 0x400 * 0x400

};

let global_allocator_physical_start = PhysAddr::new(

memory_map

.entries()

.iter()

.find(|entry| {

entry.entry_type == EntryType::USABLE && entry.length >= global_allocator_size

})

.unwrap()

.base,

);

}

Getting the virtual address of the physical memory

Now we found physical memory, but to access it, we need to access it through virtual memory. Limine offset maps all EntryType::USABLE memory. We just need to know the offset, and then add the offset to the physical memory. To get the offset, we use Limine's HHDM (Higher Half Direct Map) feature:

#[used]

#[unsafe(link_section = ".requests")]

pub static HHDM_REQUEST: HhdmRequest = HhdmRequest::new();

HHDM offset wrapper type

Our init function will need the two Limine requests mentioned earlier. The HHDM response is basically just a u64, but let's create a wrapper type so that we don't accidentally treat a diffeent u64 as the HHDM offset. Create a file hhdm_offset.rs:

/// A wrapper around u64 that represents the actual HHDM offset, and cannot be accidentally made.

/// Remember though that even though this wraps unsafeness in safeness, it is only safe if the assumption that all available memory is mapped in the current Cr3 value according to the HHDM offset (and cache is not invalid)

#[derive(Clone, Copy)]

pub struct HhdmOffset(u64);

Now let's implement the Debug trait, printing it as hex:

impl Debug for HhdmOffset {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut core::fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> core::fmt::Result {

write!(f, "HhdmOffset(0x{:X})", self.0)

}

}

To construct a HhdmOffset, we can require having a HHDM response from Limine directly:

impl From<&'static HhdmResponse> for HhdmOffset {

fn from(value: &'static HhdmResponse) -> Self {

Self(value.offset())

}

}

Now let's create a function to quickly get a HhdmOffset:

pub fn hhdm_offset() -> HhdmOffset {

HHDM_REQUEST.get_response().unwrap().into()

}

Address translation

Create translate_addr.rs:

use x86_64::{PhysAddr, VirtAddr};

use crate::hhdm_offset;

pub trait OffsetMappedPhysAddr {

fn offset_mapped(self) -> VirtAddr;

}

impl OffsetMappedPhysAddr for PhysAddr {

fn offset_mapped(self) -> VirtAddr {

VirtAddr::new(self.as_u64() + u64::from(hhdm_offset()))

}

}

Getting the offset mapped virtual address is as simple as adding the HHDM offset to the physical address.

Initializing the global allocator

Back in our memory init function, we create a slice for our memory:

let global_allocator_mem = {

let mut ptr = NonNull::new(slice_from_raw_parts_mut(

global_allocator_physical_start

.offset_mapped()

.as_mut_ptr::<MaybeUninit<u8>>(),

global_allocator_size as usize,

))

.unwrap();

// Safety: We've reserved the physical memory and it is already offset mapped

unsafe { ptr.as_mut() }

};

Then, we can give this slice to talc to use:

let mut talc = GLOBAL_ALLOCATOR.lock();

let span = global_allocator_mem.into();

// Safety: We got the span from valid memory

unsafe { talc.claim(span) }.unwrap();

Now in main.rs, after initializing the logger:

let memory_map = MEMORY_MAP_REQUEST.get_response().unwrap();

// Safety: no page tables were modified before this

unsafe { memory::init(memory_map) };

Trying it out

After memory::init, we can now use data types that need the global allocator. Try adding this:

let v = (0..5)

.map(|i| alloc::boxed::Box::new(i))

.collect::<alloc::vec::Vec<_>>();

let v_ptr_range = v.as_ptr_range();

let contents = v

.iter()

.map(|b| {

let b_ptr = &**b;

alloc::format!("Box pointer: {b_ptr:p}. Contents: {b}")

})

.collect::<alloc::vec::Vec<_>>();

log::info!("Vec: {v_ptr_range:?}. Contents: {contents:#?}");

Here we use Vec, Box, and String (which format! allocates). The output should look like this:

INFO Vec: 0xffff800000100410..0xffff800000100438. Contents: [

"Box pointer: 0xffff800000100440. Contents: 0",

"Box pointer: 0xffff800000100458. Contents: 1",

"Box pointer: 0xffff800000100470. Contents: 2",

"Box pointer: 0xffff800000100488. Contents: 3",

"Box pointer: 0xffff8000001004a0. Contents: 4",

]

We can see the pointers the talc assigned to our Vec and Boxes.

Learn More

- https://os.phil-opp.com/paging-introduction/

- https://os.phil-opp.com/paging-implementation

- https://os.phil-opp.com/heap-allocation/

- https://os.phil-opp.com/allocator-designs/

CPU Local Data

So far, we've used global variables, which are shared with all code running on every CPU, and variables inside functions (on the stack). In our kernel, we will need global variables that are unique to each CPU.

We don't know how many CPUs our kernel will run on at compile time, so we will need to allocate and initialize our CPU-specific global variables at run time. Create a file cpu_local_data.rs. Let's make a struct for keeping CPU-specific global data:

pub struct CpuLocalData {

/// Similar to [Linux](https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.6.3/source/arch/x86/kernel/apic/apic.c#L2469), the we assign the BSP id `0`.

/// For the APs, they will have an id based on their position in the CPUs array given from Limine.

pub kernel_assigned_id: u32,

#[allow(unused)]

pub local_apic_id: u32,

}

We can keep the CpuLocalDatas in an array. In Rust, we will use a boxed slice, which is basically an array allocated in run time. One question we have to answer is which CPU will have which index in the array? We can all this index in the array an ID. Limine gives us a list of CPUs, with a ACPI id and a local APIC id. However, we cannot use either of these ids as an index in an array, because these ids are not guaranteed to start with 0 and could have gaps. So we can make our own ids, which we will assign to CPUs. We can call this id kernel_assigned_id. In this tutorial, we will always give the BSP id 0, to easily recognize the BSP. We will give the other CPUs an id based on their index in the array of CPUs that Limine gives us.

Create a file cpu_local_data.rs. Let's make a struct for keeping CPU-specific global data:

pub struct CpuLocalData {

/// Similar to [Linux](https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.6.3/source/arch/x86/kernel/apic/apic.c#L2469), the we assign the BSP id `0`.

/// For the APs, they will have an id based on their position in the CPUs array given from Limine.

pub kernel_assigned_id: u32,

#[allow(unused)]

pub local_apic_id: u32,

}

For our convenience, create this helper function:

fn mp_response() -> &'static MpResponse {

MP_REQUEST.get_response().expect("expected MP response")

}

Because we only know the number of CPUs at runtime, we cay use lazy initialization to initialize an array of CPU local data:

static CPU_LOCAL_DATA: Lazy<Box<[Once<CpuLocalData>]>> =

Lazy::new(|| mp_response().cpus().iter().map(|_| Once::new()).collect());

We also need a way to store the kernel assigned id of the current CPU. For this, we need to store it somewhere that is unique to a CPU. We will use the GS.Base register for this. GS.Base is supposed to store a pointer, and this register is not shared between CPUs. We can store a pointer to CpuLocalData in GS.Base:

/// This function makes sure that we are writing a valid pointer to CPU local data to GsBase

fn write_gs_base(ptr: &'static CpuLocalData) {

GsBase::write(VirtAddr::from_ptr(ptr));

}

Next let's create functions to initialize CPU local data for the current CPU, and store the pointer in GS.Base:

/// Initializes the item in [`CPU_LOCAL_DATA`] and GS.Base

fn init_cpu(kernel_assigned_id: u32, local_apic_id: u32) {

write_gs_base(

CPU_LOCAL_DATA[kernel_assigned_id as usize].call_once(|| CpuLocalData {

kernel_assigned_id,

local_apic_id,

}),

);

}

/// Initialize CPU local data for the BSP

///

/// # Safety

/// Must be called on the AP

pub unsafe fn init_bsp() {

init_cpu(

// We always assign id 0 to the BSP

0,

mp_response().bsp_lapic_id(),

);

}

/// # Safety

/// The CPU must match the actual CPU that this function is called on

pub unsafe fn init_ap(cpu: &Cpu) {

let local_apic_id = cpu.lapic_id;

init_cpu(

// We get use the position of the CPU in the array, not counting the BSP and adding 1 because id `0` is the BSP.

mp_response()

.cpus()

.iter()

.filter(|cpu| cpu.lapic_id != mp_response().bsp_lapic_id())

.position(|cpu| cpu.lapic_id == local_apic_id)

.expect("CPUs array should contain this AP") as u32

+ 1,

local_apic_id,

);

}

In entry_point_from_limine, after memory::init, add:

// Safety: We are calling this function on the BSP

unsafe {

cpu_local_data::init_bsp();

}

And in entry_point_from_limine_mp add:

// Safety: We're actually calling the function on this CPU

unsafe { cpu_local_data::init_ap(cpu) };

Now, let's create two helper functions in cpu_local_data.rs:

pub fn cpus_count() -> usize {

mp_response().cpus().len()

}

pub fn try_get_local() -> Option<&'static CpuLocalData> {

let ptr = NonNull::new(GsBase::read().as_mut_ptr::<CpuLocalData>())?;

// Safety: we only wrote to GsBase using `write_gs_base`, which ensures that the pointer is `&'static CpuLocalData`

unsafe { Some(ptr.as_ref()) }

}

Showing the CPU in our logger

It is useful to know which CPU logged what message. Let's prefix all of our log messages with the CPU id. Let's add Color::Gray, with

Color::Gray => &string.dimmed()

for the serial logger and

Color::Gray => Rgb888::new(128, 128, 128)

for the screen. Then in the log method, add this before printing the log level:

let cpu_id = try_get_local().map_or(0, |data| data.kernel_assigned_id);

let width = match cpus_count() {

1 => 1,

n => (n - 1).ilog(16) as usize + 1,

};

inner.write_with_color(Color::Gray, format_args!("[{cpu_id:0width$X}] "));

Here we print the id (in hex) of the CPU that logged the message. We adjust the number of digits in the CPU id to be the maximum number of digits needed.

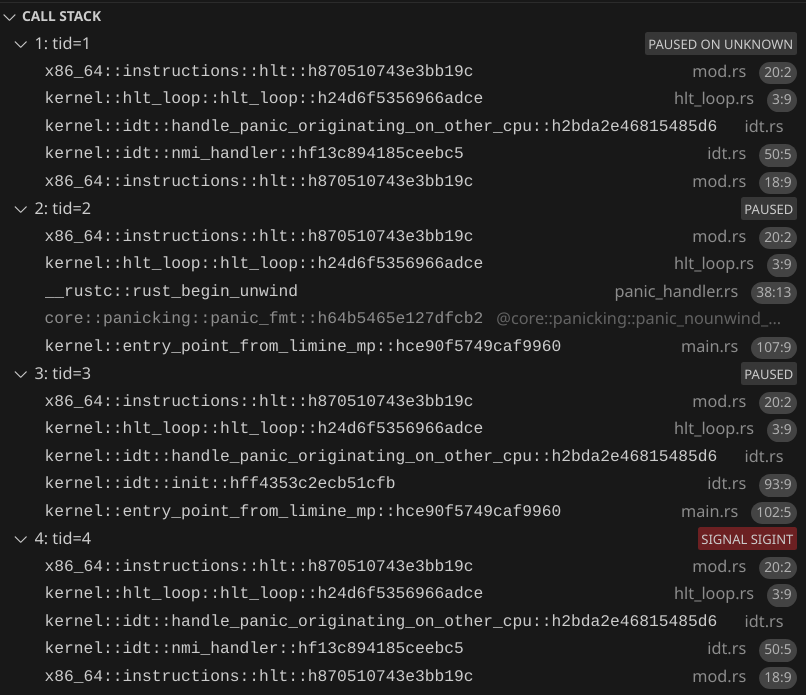

We can even try running our CPU with a ton of CPUs now. Add the following QEMU flags:

For 300 CPUs:

--smp 300

To use a non-default QEMU machine which can support this many CPUs:

--machine q35

To enable X2APIC, which is needed for >255 CPUs:

--cpu qemu64,+x2apic

To increase the memory to 1 GiB instead of the default 128 MiB, since we need more memory for all those extra CPUs:

-m 1G

Now the output should look similar to this:

[000] INFO Hello from BSP

[0C1] INFO Hello from AP

[101] INFO Hello from AP

[0BF] INFO Hello from AP

[059] INFO Hello from AP

[0A0] INFO Hello from AP

Handling interrupts and exceptions

An interrupt is when the CPU receives an external event. When the CPU receives the event, the CPU will interrupt your code and call an interrupt handler function, inputting an interrupt stack frame. The interrupt stack frame contains info about what the CPU was doing before it was interrupted, and, depending on the exception, may also contain an error code. It is the interrupt handler function's responsibility to switch back to whatever the CPU was doing before.

An exception is when the code tries to do something invalid. For example, a page fault is when code tries to access an invalid memory address. A double fault is when there is an exception that happens as the CPU tries to execute an exception handler. A triple fault happens if there is an exception as the CPU tries to execute the double fault handler. When a triple fault happens, the computer immediately reboots. Similar to interrupts, the CPU jumps to an exception handler function.

As we write an OS, there will be exceptions because of bugs in our code. We'll define exception handlers for them, because if we don't, there will be a triple fault, which is very hard to debug. We'll start by having a breakpoint exception handler. Breakpoints aren't really errors, and this "exception" is convenient to check that our exception handlers are working.

There are three things we need to set up: The GDT, TSS, and IDT. The IDT contains the handler functions that should be executed on different kinds of exceptions and interrupts. The TSS contains pointers to stacks when the CPU switches stacks before executing a handler. The GDT in modern times basically just contains a pointer to the TSS. Each CPU will have its own GDT, TSS, and IDT. Create a file gdt.rs:

pub struct Gdt {

gdt: GlobalDescriptorTable,

kernel_code_selector: SegmentSelector,

kernel_data_selector: SegmentSelector,

tss_selector: SegmentSelector,

}

We create a struct Gdt which contains the actual GDT along with segment selectors (don't worry about them).

Let's add the TSS, GDT, and IDT to the CpuLocalData:

pub tss: Once<TaskStateSegment>,

pub gdt: Once<Gdt>,

pub idt: Once<InterruptDescriptorTable>,

And make them initially Once::new().

Now we create an init function in gdt.rs:

pub fn init() { }

In cpu_local_data.rs, let's add a helper function to get the CPU's local data, panicking if it was not initialized:

pub fn get_local() -> &'static CpuLocalData {

try_get_local().unwrap()

}

Now, back in the GDT init function. Because the GDT requires a pointer to the TSS, we first initialize the TSS:

let local = get_local();

let tss = local.tss.call_once(TaskStateSegment::new);

For now, we won't put anything in the TSS, and we'll have an empty TSS. Next, we create the GDT:

let gdt = local.gdt.call_once(|| {

let mut gdt = GlobalDescriptorTable::new();

let kernel_code_selector = gdt.append(Descriptor::kernel_code_segment());

let kernel_data_selector = gdt.append(Descriptor::kernel_data_segment());

let tss_selector = gdt.append(Descriptor::tss_segment(tss));

Gdt {

gdt,

kernel_code_selector,

kernel_data_selector,

tss_selector,

}

});

Next, we load the GDT:

gdt.gdt.load();

We have to set some registers to specific values:

unsafe { CS::set_reg(gdt.kernel_code_selector) };

unsafe { SS::set_reg(gdt.kernel_data_selector) };

And we load the tss:

unsafe { load_tss(gdt.tss_selector) };

Note that we don't input the pointer to the TSS directly when loading the TSS. Instead, we input the TSS's segment selector in the now loaded GDT.

Next let's set up the IDT. Create idt.rs. First let's create our breakpoint handler function:

extern "x86-interrupt" fn breakpoint_handler(stack_frame: InterruptStackFrame) {

log::info!("Breakpoint! Stack frame: {stack_frame:#?}");

}

When we specify extern "x86-interrupt", Rust will handle restoring what the CPU was previously doing for us. It will also restore any registers that it changed. We need to add

#![feature(abi_x86_interrupt)]

to main.rs in order to use the x86-interrupt calling convention.

Next, we create a function to create and load the idt:

pub fn init() {

let idt = get_local().idt.call_once(|| {

let mut idt = InterruptDescriptorTable::new();

idt.breakpoint.set_handler_fn(breakpoint_handler);

idt

});

idt.load();

}

For now, we're only doing

idt.breakpoint.set_handler_fn(breakpoint_handler);

But later, we will add handlers for other exceptions and for interrupts.

Finally, let's call the function in entry_point_bsp after cpu_local_data::init_bsp, and in entry_point_ap after saying "Hello from AP":

gdt::init();

idt::init();

To test it out, also add

x86_64::instructions::interrupts::int3();

The int3 instruction triggers a breakpoint.

Now when we run the OS, we'll see:

[0] INFO Hello from BSP

[1] INFO Hello from AP

[0] INFO Breakpoint! Stack frame: InterruptStackFrame {

instruction_pointer: VirtAddr(

0xffffffff80013c01,

),

code_segment: SegmentSelector {

index: 1,

rpl: Ring0,

},

cpu_flags: RFlags(

SIGN_FLAG | 0x2,

),

stack_pointer: VirtAddr(

0xffff800003ba4ee8,

),

stack_segment: SegmentSelector {

index: 2,

rpl: Ring0,

},

}

[1] INFO Breakpoint! Stack frame: InterruptStackFrame {

instruction_pointer: VirtAddr(

0xffffffff80013c01,

),

code_segment: SegmentSelector {

index: 1,

rpl: Ring0,

},

cpu_flags: RFlags(

SIGN_FLAG | 0x2,

),

stack_pointer: VirtAddr(

0xffff800002634f78,

),

stack_segment: SegmentSelector {

index: 2,

rpl: Ring0,

},

}

Now that we know breakpoint handling works, let's remove the x86_64::instructions::interrupts::int3();.

Learn more

- https://os.phil-opp.com/cpu-exceptions/

- https://os.phil-opp.com/double-fault-exceptions/

- https://os.phil-opp.com/hardware-interrupts/

- https://wiki.osdev.org/Exceptions

- https://wiki.osdev.org/Global_Descriptor_Table

- https://wiki.osdev.org/Task_State_Segment

- https://wiki.osdev.org/Interrupt_Descriptor_Table

Handling page faults

Like I mentioned before, we will have exceptions, and if we can panic, log debug info, and use the debugger, we will have a much better debugging experience than if we let it triple fault.

Triggering a page fault

Let's try purposely creating a page fault:

unsafe {

(0xABCDEF as *mut u8).read_volatile();

}

here we are purposely triggering a page fault. The address 0xABCDEF is invalid, and we are reading from it. If you run QEMU now, it will triple fault, and QEMU will reboot the VM, causing an endless loop of rebooting and triple faulting. Let's do two things to make this easier to debug. Let's pass --no-reboot, which makes QEMU exit without rebooting in the event of a triple fault. And also, -d int, which makes QEMU print all interrupts and exceptions that happen. Let's add -d int to our tasks.json for convenience. Now, when we run the VM again, we should see:

check_exception old: 0xffffffff new 0xe

285: v=0e e=0000 i=0 cpl=0 IP=0008:ffffffff80007d43 pc=ffffffff80007d43 SP=0000:ffff800003be8e60 CR2=0000000000abcdef

RAX=0000000000abcdef RBX=0000000000000000 RCX=0000000000000000 RDX=3333333333333333

RSI=0000000000000001 RDI=0000000000abcdef RBP=0000000000000000 RSP=ffff800003be8e60

R8 =ffffffff80014800 R9 =8000000000000001 R10=ffffffff80016400 R11=00000000000010e0

R12=0000000000000000 R13=0000000000000000 R14=0000000000000000 R15=0000000000000000

RIP=ffffffff80007d43 RFL=00000082 [--S----] CPL=0 II=0 A20=1 SMM=0 HLT=0

ES =0000 0000000000000000 00000000 00000000

CS =0008 0000000000000000 ffffffff 00af9b00 DPL=0 CS64 [-RA]

SS =0000 0000000000000000 ffffffff 00c09300 DPL=0 DS [-WA]

DS =0000 0000000000000000 00000000 00000000

FS =0030 0000000000000000 00000000 00009300 DPL=0 DS [-WA]

GS =0030 ffffffff80019320 00000000 00009300 DPL=0 DS [-WA]

LDT=0000 0000000000000000 00000000 00008200 DPL=0 LDT

TR =0010 ffffffff80019328 00000067 00008900 DPL=0 TSS64-avl

GDT= ffffffff8001a3a0 0000001f

IDT= ffffffff80019390 00000fff

CR0=80010011 CR2=0000000000abcdef CR3=0000000003bd8000 CR4=00000020

DR0=0000000000000000 DR1=0000000000000000 DR2=0000000000000000 DR3=0000000000000000

DR6=00000000ffff0ff0 DR7=0000000000000400

CCS=0000000000000078 CCD=ffff800003be8e58 CCO=ADDQ

EFER=0000000000000d00

That's a lot of information! Here are some key details:

check_exception old: 0xffffffff new 0xe

The 0xe means that a page fault happened. You can reference this table to check the exception based on the code.

IP=0008:ffffffff80007d43 means that 0xffffffff80007d43 is the pointer to the instruction that caused the page fault.

CR2=0000000000abcdef means that the address 0x0000000000abcdef was accessed, which caused the page fault. This matches what we wrote in the Rust code.

Scrolling down, we can see check_exception old: 0xe new 0xb. 0xb means a "Segment Not Present" fault occurred. Next, check_exception old: 0x8 new 0xb. The 0x8 indicates a double fault. It seems like the double fault caused another "segment not present" fault, which caused a triple fault.

A page fault handler

Let's define a page fault handler in our IDT. Let's create the page fault handler function in idt.rs. In a page fault, we can read the Cr2 register to get the accessed address that caused the page fault.

extern "x86-interrupt" fn page_fault_handler(

stack_frame: InterruptStackFrame,

error_code: PageFaultErrorCode,

) {

let accessed_address = Cr2::read().unwrap();

panic!(

"Page fault! Stack frame: {stack_frame:#?}. Error code: {error_code:#?}. Accessed address: {accessed_address:?}."

)

}

Then let's add the function to the IDT:

idt.page_fault.set_handler_fn(page_fault_handler);

Now we should see this:

[0] ERROR panicked at kernel/src/idt.rs:17:5:

Page fault! Stack frame: InterruptStackFrame {

instruction_pointer: VirtAddr(

0xffffffff8000e220,

),

code_segment: SegmentSelector {

index: 1,

rpl: Ring0,

},

cpu_flags: RFlags(

RESUME_FLAG | SIGN_FLAG | PARITY_FLAG | 0x2,

),

stack_pointer: VirtAddr(

0xffff800003ba4ec0,

),

stack_segment: SegmentSelector {

index: 2,

rpl: Ring0,

},

}. Error code: PageFaultErrorCode(

0x0,

). Accessed address: VirtAddr(0xabcdef).

Stack Overflows

Our kernel now catches and prints errors caused by accessing an invalid address. However, there is a common type of error that our kernel does not "catch" - a stack overflow. A stack overflow is when we run out of stack memory, causing the CPU to access memory that is outside of the stack. Often, what's called a "guard page" is placed at the end of the stack. A guard page is purposely unmapped memory, so that a page fault will be triggered when a stack overflow happens. However, Limine does not set up guard pages for our stacks. This means that if a stack overflow happens, the stack could overwrite other memory, causing all sorts of unexpected behavior, exceptions, and triple faults - all very annoying to debug. For this reason, we will set up a stack with a guard page in future parts.

Learn More

Managing Physical and Virtual Memory

I will assume that you already know about physical and virtual memory, and how paging works on x86_64 to map virtual memory to physical memory. You can read the following to learn these things:

- https://os.phil-opp.com/paging-introduction/

- https://os.phil-opp.com/paging-implementation/

- https://wiki.osdev.org/Paging

So, what is the state of virtual and physical memory so far? Limine has given us a list of physical memory regions, which lets us know which ones are available for us to use. We've already used a region of physical memory for our global allocator heap. Limine set up page tables, and we have not modified them yet.

Re-organizing memory.rs

First, let's change memory.rs to be memory/mod.rs (creating a folder called memory). Then create a file memory/global_allocator.rs. Basically, move everything that used to be in memory.rs to memory/global_allocator.rs. And change the init function to return a PhysAddr. In the end of the function, return global_allocator_physical_start. In memory/mod.rs, create this fn:

/// Initializes global allocator, creates new page tables, and switches to new page tables.